Day-to-day, I’m surrounded by and immersed within my own literacy activities. I interact with texts of all kinds: whether through reading my kindle, texting my friends and family, checking my emails, reading the subtitles on a movie I’m watching, or even reading and writing the notes I’ve made upon my sheet music whenever I sit down to play. Not once did it occur to me that these literacy activities were creative in any way. Even though I interacted with these various texts every day, I never stopped to truly notice or understand the reasons why I used them or how I interacted with them, as none of these texts ever really struck me as unique or interesting. I certainly never considered them to be creative.

Upon looking more closely and carefully into how I interacted and manipulated these texts, I came to the realization that there was actually something more to be considered. At first glance, the texts involved in these literacy activities would not be considered remarkable or creative, however, the sheer nature of how I use and create them becomes the driving force behind their uniqueness. I focused my attention specifically on the annotations I have made on pages of sheet music while taking music lessons in college. This analysis offers a careful look at the annotations I made and what suddenly became visible to me once I paid close attention to my actual interactions with these texts and the processes and practices I employed for making and using them.

In their article “Creativity in Everyday Literacy Practices,” Karin Tusting and Uta Papen explore two mundane texts to provide real-life examples demonstrating their stance that everyday literacy activities can be considered creative. Tusting and Papen argue that creatively producing and using texts “is inherent and essential in people’s everyday lives” (6), thus shifting the common narrative. Creative writing, rather than being a production of an artistically stunning literary work toward one of creativity, is instead something that people routinely do in their everyday lives and that is very much a part of human existence.

In their article, Tusting and Papen begin by explaining how creativity tends to be understood. First, they examine the common definition of creativity, which centers around work or a set of works produced by someone who is a “Creative Genius,” a term coined by Shakuntala Banaji and Andrew Burn in their article “Creativity through a Rhetorical Lens” (3). Drawing from Banaji and Burn, Tusting and Papen point out that creative genius has tended to be understood as a “special quality, associated with highly educated and talented individuals, and elite artistic and cultural products” (6). For something to be considered creative, it has to possess two key characteristics laid out by Banaji and Burn. First, it would need to be regarded as artful, which means the creation of something aesthetically pleasing. Second, it would need to be regarded as original in the sense that it had never been created before. Tusting and Papen emphasize how these characteristics serve as the central features of determining whether a work is creative. Tusting and Papen also highlight another viewpoint commonly heard in the discussion of creativity, “democratic creativity,” which can be defined as a creative work that “highlights the existence of similar ‘creative’ aesthetic features in popular cultural products and patterns of cultural consumption” (6). This type of creativity follows the set of characteristics listed above and, in turn, reinforces the narrative that creativity is a talent only a few can possess.

Tusting and Papen, however, argue in favor of a different definition of creativity, venturing further into the topic of creativity literacy. In contrast to typical ideas of creativity, they argue that “creativity is seen not as the privilege of the particularly gifted, but as a common, everyday occurrence” (7). In this sense, creativity is something that everyone engages with on a daily basis. It’s not rare; rather, it’s commonplace in people’s endeavors. In other words, as Tusting and Papen argue, creativity “does not necessarily have to refer to making something startlingly original, apt, witty or playful, but can simply mean the human capacity for making meaning in a situation where no communication existed before” (7). Their stance challenges the core of what is usually considered creative.

To further explain their argument, Tusting and Papen discuss creativity in terms of bricolage, a term which means “making do by putting together whatever is at hand” (7). A bricoleur practices bricolage and “creativity lies in the bricoleurs’ ability to capture or imagine the potential of the things they find in their environment” (7). Suddenly, the meaning and connotations behind the term “creativity” shifts. The creativity in a task lies in the person’s ability to reimagine the potential of their surroundings and the way a person engages with such things. So, in turn, the everyday literary practices engaged with even in the smallest parts of one’s life are now included in the narrative of creative works.

For Tusting and Papen, adopting this alternative notion of what creativity is and how we think about it greatly expands the kinds of texts people create and use, and textual practices they employ to make and use them. As they state:

Looking at how people produce and use texts, we identify the creativity inherent in seemingly mundane forms of written communication, even where the texts themselves might show little evidence of the language features normally associated with ‘artfulness’. Rather than exploring language features and categorising texts in terms of their relative creativity, we will argue that text production practices are intrinsically creative. (7)

In this analysis, I take up Tusting and Papen’s definition of creativity to examine the creativity of my own mundane texts that I engage with on a daily basis—sheet music that I annotate. At first glance, my annotated sheet music may not seem creative; however, I argue that these texts. My process of taking a musical score and marking it to enhance my ability to play it is highly personal. Though most musicians annotate their sheet music, it is still a highly individualized, creative practice.

Methods

In their article, Tusting and Papen describe their use of ethnographic methods, defined as “detailed observations of and participation in social practices over time” (8), in order to understand how two ordinary texts—a weekly church bulletin assembled by a church secretary in England and a sign for a campsite designed and crafted by citizens of a small village in Namibia—were created and interacted with on a daily basis. Using an ethnographic approach gave Tusting and Papen a chance to “systematically record and describe any literacy-related activities in the context of the social practices of which they are part” (8). Their main source of data was a series of unstructured interviews with the texts’ creators, where Tusting and Papen were able to talk with the person(s) involved in creating the bulletin and the campsite sign to get a sense of their intentions and point of views towards the texts they were creating, the sources and materials they drew from, the many decisions involved in selecting from and assembling those sources into a single text, and the rationale behind those decisions. By talking with the people who created the church bulletin and the campsite sign, Tusting and Papen developed a fine-grained sense of how each of those texts were created and the intentions underlying the author’s decisions in making them. Ultimately, Tusting and Papen’s use of ethnographic methods illuminated how the creativity involved in these texts is “socially shaped” and how “people draw on the semiotic resources available to them in creative ways to fulfil [sic] the demands of particular situations” (8).

To examine my sheet music, I drew upon Tusting and Papen’s careful attention to how ordinary texts are created and used. However, where Tusting and Papen used an ethnographic approach to study and analyze ordinary texts created and used by other people, I adopted an autoethnographic approach to study texts that I created and used. Borrowing Tusting and Papen’s research methods, I used a similar technique of observation that involved gathering some of the pieces of sheet music I used, taking a close look at the annotations I made on them, and questioning my reasoning and intentions behind the marks that I made. For each piece of sheet music I examined, I also recalled how I used the annotations I made as I practiced and performed each piece of music. In other words, I became the observer of my annotated sheet music, noting what the annotations meant to me as a musician playing these pieces of music. In doing so, I stepped into the role of an autoethnographer. Autoethnography allows a person “to present their [own] experience in the context of relationships, social categories, and cultural practices and this method revels in sharing insider information about a phenomenon” (34). Through the method of autoethnography, I am able to share how I relate Tusting and Papen’s definition of creativity with my own literacy-related activity: annotating my sheet music. My methods of research encompassed more than self-assessment, which allowed me to move into other areas of inquiry. I began to compare my annotations based upon different instruments used and the specificity of my annotations to the instrument. I also recognized the influence previous music teachers had and how the teacher’s annotations had an influence on my own style of annotations.

Analysis of My Annotations

Just like the routine of the person who authored the church bulletin each week in Tusting and Papen’s “Creativity in Everyday Literacy Practices,” musicians have a routine every time they sit down with a new piece of music to learn. I must take note of tempo, phrase marks, notes, music keys, and anything else that cues me in as to how I need to make the piece sound. Little blurbs to the side of the music are placed on my pieces of sheet music to remind me what I need to look out for as I play, i.e., the key the piece is written in or circling around the tempo as to not forget how fast or slow to play. Then, as I play through the piece, I notice hiccups or places I get repeatedly stuck in. These problem areas require me to scribble in reminders to myself to look ahead or work through that section until I feel comfortable playing it all the way through without hesitation.

Below, I examine annotations I made on five different pieces of sheet music I’ve worked with while learning to play marimba, concert snare drum, and voice. The first annotations that I examine are ones that I made on a piece of music while learning to play the marimba for two semesters in my sophomore year of college with a professional marimba teacher. A marimba is a percussive instrument made of wooden bars that are struck with yarn mallets to produce sounds heard on the chromatic scale. To help me improve my playing skills with the marimba, my teacher would assign me practice scales and tunes to work on each week from a practice book.

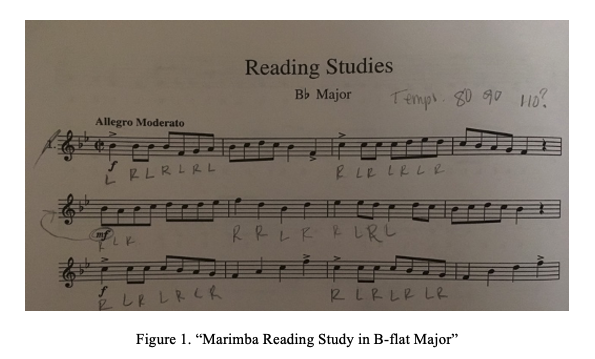

One week, my teacher asked me to work on a piece from a book titled Reading Studies (figure 1), which offered an opportunity for me to work on the scale of B-flat major, a key step toward becoming proficient in playing variations of the B-flat major scale. Music scales are the building blocks of musicianship, and I had several other practice excerpts within this book exactly like the one pictured in figure 1 so that I could practice all of the scales.

While working to learn this piece, I made a number of annotations on the page. The image in figure 1 includes several of the different markings I made, including tempo markings (top right), stick pattern markings (indicated by the series of “L R L R”), and an arrow I drew in that points to the dynamics on the far right of the second line of musical notation.

Some of the most important markings to consider in this figure are the indications of “L, R, L, R.” This simply means “left, right, left, right.” When playing the marimba, it is important to play each note with the proper hand, known as a sticking pattern. Correct sticking patterns mean the difference between playing correctly or poorly. It becomes easy to start crossing the left and right arm over each other while playing, and one can become physically tangled up. The main goal is to play smoothly with the sticks following through a pattern on a string of notes without hesitation of an awkward or misplaced hand. For me to play this piece correctly, I needed to form the habit of correct sticking patterns through regularly notating them on my sheet music.

These patterns are different for each piece of music learned on a marimba. Each piece requires a different sticking pattern depending on the position of each note. I typically start out by sight-reading and playing the piece, and then the physical notations I write on the piece follow soon after. I notice how the patterns feel with the mallet sticks in my hands and write my hand patterns down as I go. Once I begin writing down these notes, the patterns usually fall into place pretty quickly; however, there are some pieces where the patterns aren’t obvious and may require more work, needing such solutions as a repeated “left” or “right” next to each other. The annotations soon turn into “mental notes,” where I’m able to memorize the annotations and, in turn, play the piece faster and with more precision. Sticking patterns notated upon sheet music can be a common way to annotate for percussive instruments. Since marimba is a part of the percussive instrument family, sticking patterns are important. I make a specific point of these annotations I marked throughout this piece because these are not markings I would make upon other sheets of music for instruments, like piano or voice. This sheet of music didn’t give me indications of where to place my “L” and “R” markings; they are up to my own discretion.

According to Tusting and Papen’s definition of creativity, the markings I made upon my marimba practice reading are creative. They give new meaning to the sheets of music I am using. These sheets are no longer what they once were to me but have taken on an enhanced meaning specific to myself and my learning. Before my annotations, the sheets of music are just that—sheets of music—but when I write my notes on them, the sheets become strictly my own.

The second set of annotations I examine are from one of my rhythmic practice books for concert snare drum called Intermediate Snare Drum Studies by Mitchell Peters. I began concert snare drum lessons in my sophomore year of college—learning this instrument was incorporated into my percussion lessons. My percussion lessons were broken up into categories involving either marimba or concert snare drum.

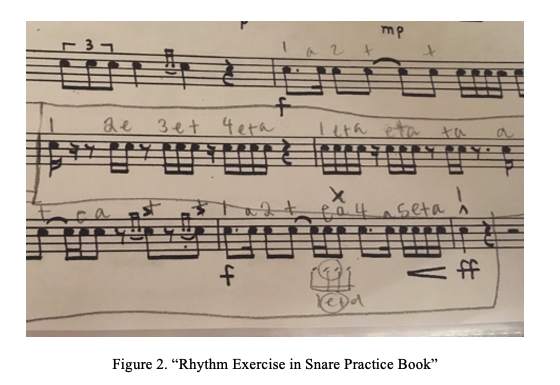

The first item of business when learning snare drums is learning rhythms. I began learning different and complex rhythms and how to count and play these rhythms, which proved difficult. Since playing rhythms was new to me, I needed extensive practice knowing what rhythms looked like written out. My instructor guided me by assigning basic pieces, like the one in figure 2, to give me a solid rhythmic foundation as a musician.

I was a beginner at the instrument, so I wrote out how I would count the rhythms as I played the piece. In the last line of music on the sheet music, I wrote out the basic counts of the rhythms, starting with “+, e, a” (sounded out as “and, e, uh”) and ending with “5, e, +, a” (sounded out as “five, e, and, uh”). For each beat, I wrote an annotation above to help my mind form an understanding of what these rhythmic notes would sound like out loud. Doing so helped me, as I played with more difficult rhythms. I chose this piece to showcase the difference in markings between sheet music meant for the snare drum versus the marimba versus voice.

I must take note of tempo, phrase marks, and anything else that cues me in as to how I need to make the piece sound. I have written out the verbal “counts,” or how I would count the beat out loud for each bar of music. This mnemonic device is how musicians are taught to count rhythms while playing music. Verbally counting out the beats helps me internalize how these rhythms go, so in the future, it becomes second nature to play, and I won’t need to verbally count them out. These written markings help me remember how to count out the rhythms in my head as I play each section. These markings greatly improved my ability to play rhythms. Breaking down each note into how to count it mentally is now a permanent fixture in my head each time I play a rhythmic piece. It’s important I had annotated this into my sheet music because, at the time, I needed to work on memorizing the basic counts of rhythms and how each note fit into each bar of the music.

My annotations are markings that only I know the true meaning of, and writing them should be quick as I practice. I have developed a new text that I am the sole creator of, and only I know the meaning behind each note or mark I have made and how it relates to the original sheet music. These markings are creative to how I practice music and how they help me as a musician learning music.

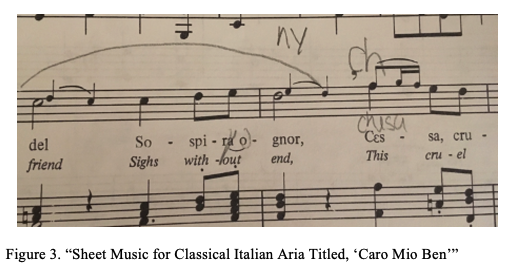

The third set of annotations I examine are ones I jotted on the musical score for a classical Italian aria called “Caro Mio Ben” by Giuseppe Giordani that I was learning to sing for a recital performance (figure 3). I was practicing this aria in my freshman year of college and I was in my second semester of voice lessons. As part of my voice lessons, I was assigned different genres to sing, and this is how I learned different techniques with my voice and how to sing different styles, such as musical theatre, classical, and contemporary. Fine-tuning each detail, all the way down to the vowel annunciation, greatly helped me as a musician. This piece was difficult for me to learn because I had problems with the pronunciation of different words in the aria.

This particular sheet of music is in Italian. Since I don’t speak Italian, I had to learn inflections of the language and how certain vowels are pronounced. In figure 3, I wrote out and emphasized the “ch” sound in the Italian word “cessa.” Without this certain annotation I’d made, I most likely would have forgotten the emphasis needed for this pronunciation, thus learning the piece incorrectly.

Since every musician has different learning styles and memory capabilities, the markings are most likely also different from one musician to the next. Note the penciled line starting at “friend” and ending at “end.” This is a phrasal mark I wrote in to show the phrasing for this section of music. I know to take a breath before “friend,” and this breath will sustain me for the phrase showcased in figure 3. After “end” and before “this,” I will take another breath to sustain the next phase of music. Phrasal marks must be strategic when singing to ensure there is enough breath support for each section of the song. Taking breaths in between phrases can make the voice sound choppy and is noticeable to the listener.

In reference to Tusting and Papen, I annotated my sheets of music in “creative ways to fulfil [sic] the demands of particular situations” (8), the particular situation being marking my sheet music for my voice lesson. Only I would mark these little cheats because these are the words I had trouble with while rehearsing the piece. Not only are my marks particular to each different instrument I am playing, but they also differ between musicians. Individually, each musician has their own issues that need to be worked through.

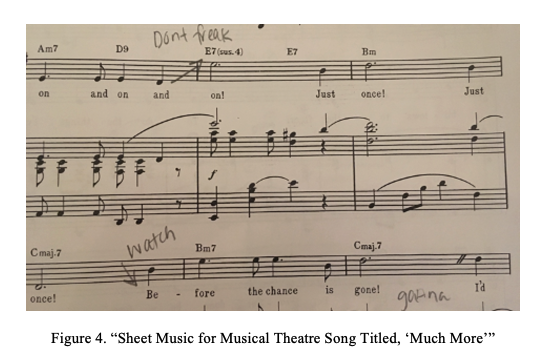

The fourth set of annotations I examine are the ones I made on a piece from the 1960s musical The Fantasticks titled “Much More” (figure 4). My instructor gave me this piece to help broaden my scope as a vocalist.

The words “don’t freak” written at the top of the figure indicate an octave coming up in the piece. I wrote this because I had a habit of psyching myself out when I would get to this section. This was a written reminder as I approached this section to not be afraid of the octave jump I was about to sing. I also wrote “watch” towards the bottom. This annotation helped me sing on the correct beat because I had a habit of forgetting to come in after finishing my last phrase. The marking indicated to me to watch out for the next phase coming up. The markings I made were during a lesson with my voice instructor. Each word I wrote was a verbal note from my voice teacher, as she was able to notice the places I needed extra help in.

I chose this text to show the active part others play within our everyday literacy activities. My annotations are a cumulation of all my years of music lessons and my ability to respond to the instruction I received in each lesson. Each piece of music I have referenced has been influenced by the different music instructors I have encountered throughout my lifetime.

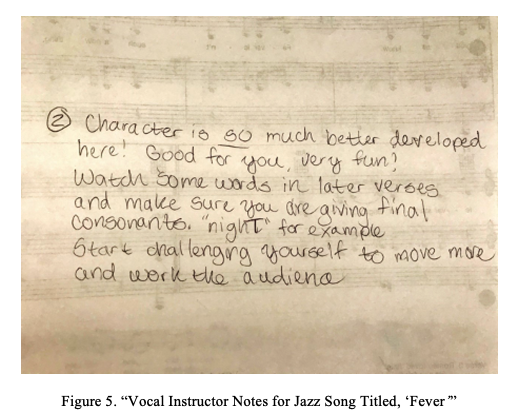

The final set of annotations I examine (figure 5) are notes my voice instructor wrote for me during a practice performance of one of our lessons together for the jazz piece called “Fever,” written by Eddie Cooley and Otis Blackwell. Character development is important as a vocalist, especially in this piece as expressions and mannerisms are part of the performance of the song.

This jazz piece brought me out of my shell in terms of confidence and was challenging at first to learn. Not only was the character important, but also the way I enunciated the words in the song. Notice in the paragraph my instructor emphasizes “final consonants” in the word night as an example. I was cutting off the end of words as I would sing them, causing the audience to not hear the words as I sang them. To help correct this, my instructor wrote down this note so I wouldn’t forget this as I sang. These notes in figure 5 soon transformed into mental notes for me as I kept practicing. This is a great example of co-authorship. I chose figures 4 and 5 to display how co-authorship takes different forms in the annotations of my music. They can be verbal instructions, which I write down on my sheets of music in a way I want to remember, or they can be direct quotations from the instructor on the backs of my sheet music.

This unique situation of collaboration is a great example of Tusting and Papen’s definition of creativity. My instructor giving me feedback on my performance is a correction that changes the nature of my physical performance of the song and the mental notes I chose to write down to remember. We worked together to mold this sheet of music into a performance tailored to me as the performer. Each sheet music may be the same at the beginning of learning the music, but as the musician and instructor dive deeper and hash out the nuances of the piece, the annotations and learning of the piece evolves. We create meaning with our marks on the scores.

Conclusion

Each of the examples I provide conveys the message I’d like to make, which is that creativity is more than meets the eye. Creativity spans beyond the notion of new and completely original and into the realm of the nuances and personal interactions others have with their own literacy activities every day. There is a takeaway from each snippet of sheet music I showed above. The marimba sheet music (figure 1) showcases the differences in markings I made upon that sheet music versus others for different instruments. The snare drum excerpt (figure 2) shows how the markings I make are specific to me and how they help me as a musician learning music. Many others have practiced the same excerpt, but only I creatively chose to write down those markings to aid my learning. “Caro Mio Ben” (figure 3) is an example of another element of creativity within my sheet music. The problems I encountered in this example were personal to me as the performer. To enhance my ability to sing this aria, I needed to write personal notes to myself; these notations transformed this sheet music and aided in my personal journey of learning the aria. The excerpt from the musical Fantasticks (figure 4) and the instructor comments for “Fever” (figure 5) touch base on the circle of life as a musician. Everything is connected, and knowledge is passed down through the technique of annotations and little markings on my own sheet music. The collaboration between musician and instructor offers up a world of endless creativity, as they both work together to create a musically stunning performance and hone the craft of a musician.

Analyzing my own sheet music has given me a new perspective on what defines creativity. In the beginning, the thought of my sheet music being creative in the common notion of creativity didn’t make sense. But, as I read through and understood the perspectives of Tusting and Papen, I was able to see through their lens of creativity, and the new door of possibilities showed itself. As I interact with these texts now, I feel a deep sense of gratitude for this new possibility. Tusting and Papen’s definition makes my world of literacy much more colorful and vibrant, and no longer do ordinary texts strike me as mundane or not worth anything. They are worth everything, and they are worth exploring.