In her book Between Talk and Teaching: Reconsidering the Writing Conference, Laurel Johnson Black uses transcript analysis to study the elements of discourse present in student-teacher writing conferences. The goal of a student-teacher writing conference is a one-on-one session, in which the teacher helps the student. In her research, however, Black finds many patterns of speech that work contrary to this goal. These patterns are not present because the teachers are deliberately working to inhibit student learning; the teachers are unaware of the effect their speech is having on the students they work with. This is because they have not taken a step back to examine their patterns of speech and the effects those patterns have on the students they work with (Black).

While different from a student-teacher writing conference, writing center sessions also suffer from a disconnect between a tutor’s goals and their patterns of speech. My goal as a writing center tutor is to facilitate learning for the writer. I often find myself feeling unsure after my sessions, wondering if I am achieving this goal. To find out, I recorded one of my sessions to use as a case study of my writing center speech. I then transcribed this session using Gilewicz and Thonus’ method of close vertical transcription, capturing “the reality that several speakers may share a channel… [and adding] rich detail for interpretation of writing center interaction” (30). Through the analysis of this transcript, I aim to take a step back—as Black did—and examine whether my patterns of speech are helping me achieve my goal of student learning or inhibiting me.

In addition to using the elements of discourse defined by Black, Gilewicz and Thonus to analyze my transcript, I also intend to analyze it through the lens of Andrea Lunsford’s styles of writing center. In her piece “Collaboration, Control, and the Idea of a Writing Center,” Lunsford writes about three kinds of writing centers: Storehouse Centers, Garret Centers, and Burkean Parlors. She defines Storehouse Centers as “tend[ing] to view knowledge as individually derived and held, and they are not particularly amenable to collaboration, sometimes actively hostile to it” (Lunsford 5). While knowledge is viewed as exterior in a Storehouse Center, Garret Centers are the opposite, with knowledge viewed “as interior, as inside the student, and the writing center’s job [is] helping students get in touch with this knowledge, as a way to find their unique voices, their individual and unique powers” (Lunsford 5). Lunsford holds the third style, the Burkean Parlor, above the others. Lunsford claims that Burkean Parlor Centers, which utilize a style of tutoring with an emphasis on collaboration, are necessary to “meet the demands of the twenty-first century” (8).

Garrett Centers are “informed by a deep-seated attachment to the American brand of individualism” (Lunsford 5), and emphasize the writer as holding individual knowledge that only they can access on their own. However, Lunsford found in her research that the data supported what students had been telling her for years; “their work in groups, their collaboration, was the most important and helpful part of their school experience” (5). As such, Lunsford advocates for writing centers to strive to act as Burkean Parlors, while also acknowledging that creating a collaborative environment is “damnably difficult” (6). In my analysis, I will examine what patterns of speech create what style of tutoring, based off of Lunsford’s definitions. I hope to identify patterns that can be used to create the troublesome Burkean Parlor, with the intention of applying them to my future tutoring sessions.

In my case study of writing center speech, I worked with a writer who wanted help with a paper for her theatre class. It was a show paper analyzing Sweat, a play she saw at UCF. She had already written her paper a week or so before coming to the writing center; she just wanted someone to look it over before she submitted. During the session, I was able to establish good rapport with the writer by making conversation with her based on our shared knowledge of theatre. I also encouraged the writer by frequently backchanneling—making sounds to show I was actively listening—throughout the session, encouraging her as she worked through her problems on her own. As I was letting the writer be in control, she engaged in the most topic initiation, using her knowledge of the class and the paper she had written to direct the session. The writer and I both used questions throughout the session. I used leading and scaffolding questions, which are queries designed to encourage the writer to think, in an attempt to facilitate learning. However, the writer frequently responded to these questions with descriptions of uncertainty, an indication that my questioning was ineffective. When the writer would in turn ask me questions, I responded with my own descriptions of uncertainty, hesitant of just giving her the answer and not allowing her to learn for herself. My patterns of speech in this session created a Garret Center session, where I spent the entire time encouraging the writer and prompting her with questions instead of creating opportunities for her to learn.

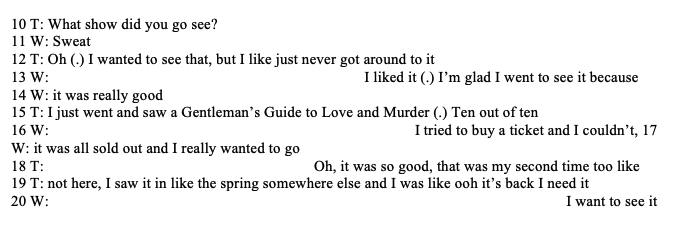

I started off the session by establishing rapport with the writer, creating a relationship based on our shared interests. As she was pulling up her paper for us to look at, we talked about different shows we had seen or wanted to see.

At this point, the session was conversational, which can be seen in the interruptions the writer and I both used. “Conversational contributions often overlap… Interruption is defined as the initiation of a contribution by a second party before the first has finished” (Gilewicz and Thonus 35). The writer and I are both interested in theatre, so we are both excited to have a conversation about the topic. She interrupts me in lines 13, 16, and 20, eager to express her opinion on the matter. I interrupt her in line 17, also passionate about the subject. These interruptions can be seen as cooperative overlaps, which “indicate shared knowledge” (Black 67). The shared knowledge the writer and I discussed allowed us to get acquainted quickly; we related to each other because of our common interest. “According to several studies, engaging in small talk can lead to greater satisfaction for tutors and writers, and not doing so can lead to unfulfilled expectations for both” (Fitzgerald and Ianetta 57). This conversational talk with cooperative overlaps helped the writer and I “build a working relationship” (57). Establishing good rapport can aid a tutoring session of any style, whether Storehouse, Garret, or Burkean Parlor. In my case, these patterns of speech throughout my paper where I converse casually with the writer about topics other than her writing aided my role as a Garret Center tutor. By establishing a good working relationship with the writer, she trusted me to encourage her throughout the session to unlock the knowledge she needed for her writing.

I encouraged the writer’s control of the session by frequently backchanneling. Backchanneling consists of “contributions made by other participants while the first speaker holds the floor” (Gilewicz and Thonus 29). These contributions provide “agreement or support” (Black 49) for the speaker, encouraging them to continue with their thoughts. Backchanneling is also a way of demonstrating active listening. “Most people want to be heard… by listening, a tutor creates another opportunity for the writer to engage in the session because it can demonstrate to the writer that she can have a say in the direction of the conversation” (Fitzgerald and Ianetta 63). In this less than twenty-minute session, I used backchanneling a total of seventeen times.

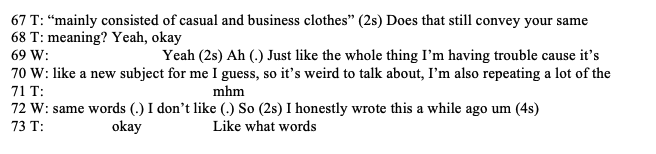

In line 71, I backchannel “mhm” as the writer hedges—a way of indicating uncertainty (Black 67)—with “I guess.” I encourage her to keep talking despite her hesitancy, and by demonstrating active listening, I engage the writer and let her keep control of the conversation. I also backchannel in line 73, acknowledging the writer’s hesitancy again with “okay.” This pattern of backchanneling when the writer is hesitant furthered my role as a Garret Center tutor. Garret Center tutoring is acted out when “the tutor or teacher listens, voices encouragement, and essentially serves as a validation of the students’ ‘I-search’” (Lunsford 5). By encouraging the writer when her speech is unsure, I am validating her and encouraging her to stay in control.

Once we began actually discussing the paper itself, the writer was in control of what we focused on in her text. While I may initiate a topic twelve times in the transcript compared to her eight, four of my initiations occur prior to looking at the paper itself, such as determining what assignment she came in to work on as well as further context. Additionally, three of the topics I initiate in the session are conversational and not related to the writing itself. In comparison, all of the topics the writer initiated related directly to her writing, such as asking about grammar, word choice, sentence structure, and reader understanding. We never set a formal agenda, instead meandering through the paper as the writer found concerns she wanted to address.

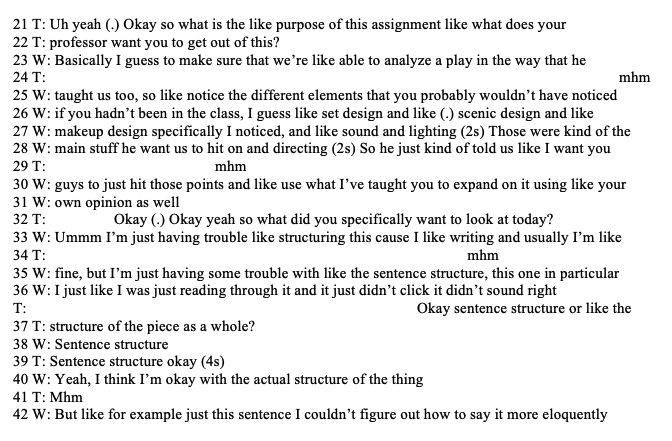

I take the time to get to know the context of the paper, as seen in line 21 where I ask her what her professor wants her to get out of this assignment. Then, instead of reviewing her writing in relation to this context and taking the time to identify any global-level concerns, I immediately put the pressure on the writer to be in control of the situation by asking her what she specifically wanted to look at in line 32. The writer then brings up the topic of sentence structure, a sentence-level concern. She focuses on sentence-level concerns throughout the paper, understanding “the revision process as requiring lexical changes but not semantic changes” (Sommers 382). This is common among student writers. “Because they are still seeing the text as a product, even when they are told they are dealing only with first drafts, as readers students focus their attention on surface-level, local, lower-concern types of problems. Their impulse is to ‘fix’ what they read” (Gilewicz 67-68). We spent the entire session fixing the paper instead of truly revising it because I was acting as a Garret Center tutor. I did not want to push the writer to do something she did not want to, or make her feel I was wasting her time by harping on context if she did not think she needed to. Black writes about how typically, “the teacher controls the topic and access to the floor” (81), and being a teacher was exactly what I was trying to avoid. I let the writer be in control, so she revised in the way she knew how.

The writer and I both asked questions throughout the session, however, my questions clearly dominated, as I asked twenty-two questions to her ten. According to Thompson and Mackiewicz, “Questions in writing center conferences serve a number of instructional and conversational functions” (37). One of the most common types of questions they identified was leading and scaffolding questions. I asked the writer many scaffolding questions, “questions pushing [the student] forward in revising or brainstorming” (Thompson and Mackiewicz 43). However, the questions I asked did not evoke my desired response from the writer; rather than brainstorming and coming to her own conclusions about how to revise, she would respond to me with descriptions of uncertainty. She would ask me knowledge deficit questions, “questions obtaining information that [the tutor] or [the student] genuinely does not know” (Thompson and Mackiewicz 42). In response, I would hedge my answers to those questions, not wanting to take a learning opportunity from her but misunderstanding what the writer needed from me.

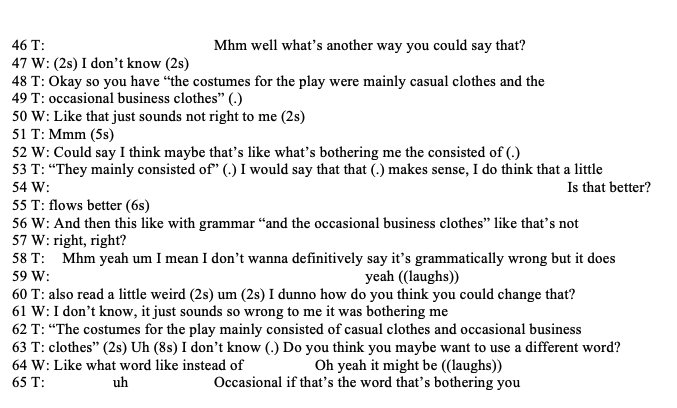

In line 47, the writer responds to my scaffolding question of “well what’s another way you could say that?” with “I don’t know,” a description of uncertainty that Black sees as “defeat, frustration, avoidance, and resistance” (62). This is an indication that the question I asked isn’t effective; the writer is not learning anything from this line of questioning. Despite this, I asked essentially the same question in line 60, saying “how do you think you could change that?” Because I was unaware of the effect my questions were having within the session, I continue to do what I know and question the writer, prompting her to come up with her own solution. The writer continues to indicate her uncertainty to me by asking the knowledge deficit question “is that better?” in line 54 and “like that’s not right, right?” in lines 56-57. I responded to her questions with hedging and lots of wait time. In line 53, I hedge with “a little,” afraid of giving the writer faulty information. In line 58 I hedge again, saying “I don’t wanna definitively say.” These hedges serve to soften my language, keeping me from sounding confident and absolute. The hedging serves as a safeguard, so that if the writer later finds out that something I told her is wrong, she will remember that I was not entirely sure in the first place. In line 63, I use eleven seconds of wait time, interspersed between “I dunno” and “uh.” I am uncertain and resistant, not knowing what to say without either possibly giving out false information or, if the information happens to be correct, giving away information that I should be helping the writer to learn for herself. Rather than giving the writer a straight answer, I ask her another question, a leading question: “do you think you maybe want to use a different word?” My questions are not facilitating learning for the writer. Instead, I am again acting as a Garret Center tutor, trying to draw the solution out of the writer instead of working with her to figure out the answer together.

Throughout the entire transcript, my patterns of speech are indicative of Garret Center tutoring. By establishing rapport and backchanneling with the writer, I set myself up to have the writer’s trust so as to help her access her own knowledge most effectively. However, Garret Center tutoring was not effective in this session; my speech was not aligning with my goal. The writer would ask me knowledge-deficit questions and I would become flustered and uncertain, hedging and thinking wildly of other questions I could ask to lead her to the answer herself. Instead of focusing so much on leading the writer, I should have been working to collaborate with her. Had I achieved Burkean Parlor tutoring and worked together with the writer, I could have brought my knowledge of expert revision to the session and kept us from focusing only on sentence-level errors. Then, the writer might have learned something.

In the future, I will continue to work to establish good rapport and backchannel with my tutees. Establishing a good working relationship is beneficial in any tutoring session, regardless of style. However, in order to work toward Burkean Parlor tutoring, I will be less hesitant to initiate topics related to the writing of the paper. By collaborating with the writer to set a formal agenda at the beginning of the session, I will be able to bring up concerns based on my background knowledge of how professional writers revise as well as addressing any concerns the writer may have with their writing. This will not only make the session more collaborative but also more effective, as global-level concerns are more likely to be addressed. In my future sessions, I will also be more direct with writers, using imperatives instead of asking questions. “Using imperative sentences often invites longer, more reflective responses” (Johnson 34). Rather than receiving a frustrated “I don’t know” from a writer, I will be more likely to get thoughtful responses by using imperatives and being direct.

While this seems somewhat contrary to Burkean Parlor tutoring, collaboration means both people bring different strengths to the table. As the one with more revision experience, I need to be confident enough to direct the writer on how we should approach their paper. The writer needs to trust in what I direct them to do, just as I have to trust in their knowledge of the class and the parameters of their assignment. Had I collaborated with this writer to set a clear agenda based on both our concerns, and had I been more direct with my language, the session would have gone differently and been much more effective. However, I do plan to still try and incorporate scaffolding questions into my tutoring. Each session is unique, and just because scaffolding questions did not work for this writer does not mean they will be ineffective for another writer. What is most important is that I pay attention to how my speech affects the session and affects the writer, so I can prevent the disconnect between my goals and my speech.