I sat quietly in my classroom, planning for the upcoming recital. The door slowly crept open, and a herd of five-year-old children swarmed at my ankles. They tugged on my shirt and screamed, “Ms. Kealani!”. This is the usual scene at my job, as a studio dance teacher and assistant. After graduating high school, I found myself wiping boogers off of three-year old children and chaotically scribbling in my notebook, trying to keep track of choreography for my teachers. Within my first year of working, I assisted eight baby classes. My notebook became the source of my livelihood, and all its contents were the substance that kept me equated with abundant number of dances throughout the year. Slowly, I built a reliance on these texts I created, and my confidence as an assistant became contingent upon creating them. It was my ability to create notes that were comprehensible not only for my own understanding, but for my teachers; that opportunities to become a working teacher myself became readily available. I never thought that dance would require so much writing, and how integral that writing was to success as a dance teacher.

Now, at twenty-one years old, I have been working as a dance instructor for three years. I have worked with children from as young as fifteen months old— those who are still exploring the idea of walking in place of crawling, to middle school and high school students who take dance after school. From ballet, tap, jazz, and tumble, I have worked many classes as an assistant teacher and eventually I’ll be teaching my own Broadway baby classes (children ages three to six) in a few years at my studio. I have experienced classes of fifteen twelve-year old kids still learning the basics like moving their hips to music or jazz walks; to competition kids who require much more intense conditioning and training. Broadly speaking, I have grown so much as not only a teacher, dancer, and studio instructor, but as an individual. As a historically shy and quiet person, teaching has pushed me to speak louder and be more confident with having my presence known in a room of dancers. Oddly, the one area that reflects this growth are my years of dance notes. My confidence hinges upon the notes I create in the studio. This reliance on the texts I create, from choreography notes to lesson plans, reflect my ability to stimulate an engaging class, and consequently the authority I embody as a teacher.

Upon looking at a few years of my notes, I became curious of the scholarly conversation of dance literacy and more importantly, dance text. When looking into the presence of literacy in dance, I became overwhelmed by the notion of choreography as language and the idea of embodied literacy as a dancer. Researchers in the field of dance literacy contribute to the conversation by studying the creative and demanding physical processes that dancers train through as well as how choreography can communicate to audiences, from creator to observer. Scholars understand a dancer’s sense of literacy comes from kinesthetic abilities, aural understandings of patterns, and bodily awareness (Riggs; McGregor). Many have mentioned the presence of text, as a source of inspiration for choreographers, or in the drawings of children in dance classrooms (Eva; Harvey). Writing researchers have also weighed in on the discussion by making parallels to the drafting process and the artistic components of text to the processes that a choreographer or dancer often experiences in performance (Corbrett; Daniels; McCarroll). Specifically, the studies of Daniel, hold a significant role in the structure of my study of dance text.

While acknowledging dance is a physical artform, these conversations lack in physical text that are used in everyday dance classrooms. Interestingly enough, these dance texts are accumulated throughout every dance class, by both teachers and students. The gap in scholarly conversation lies in the studies of physical text in the dance world. While reflecting back on the years of dance notes that I have compiled as both instructor and assistant, I was surprised that literacy researchers have neglected the presence of inscriptions created by users, observers, and creators of dance. This is where I chose to use the inscriptions created in my workplace to better understand the impact of physical text in a dance environment.

This is my study of my personal experience with dance inscriptions and the importance of inventing, revising, and performing of dance notes as a studio instructor. As scholar Cobrett has noted many times in her analysis of performing choreography, creating a dance parallels the creative process of a writer. Drafting, revision, collaboration, deliverance, and in the case of a dancer, performance, are all essential steps in the creative choreographic process. Throughout this paper I will go through several examples of my choreography notes to demonstrate how dance and writing are paralleled artforms. Most importantly, how writing at my job as a dance instructor is a beneficial and functional practice. The term functionality is a key term I use to define how dance inscription aids in memory retention, the choreographic process, and enhancing performance quality. Ultimately, my analysis of dance text as a studio instructor will prove the necessity of text in the realm of dance for its functionality throughout the multiple stages of choreography; of inventing, revising, and performing.

Invention: A Draft for Memory Retention

Figure 1. Front and back of coloring sheet

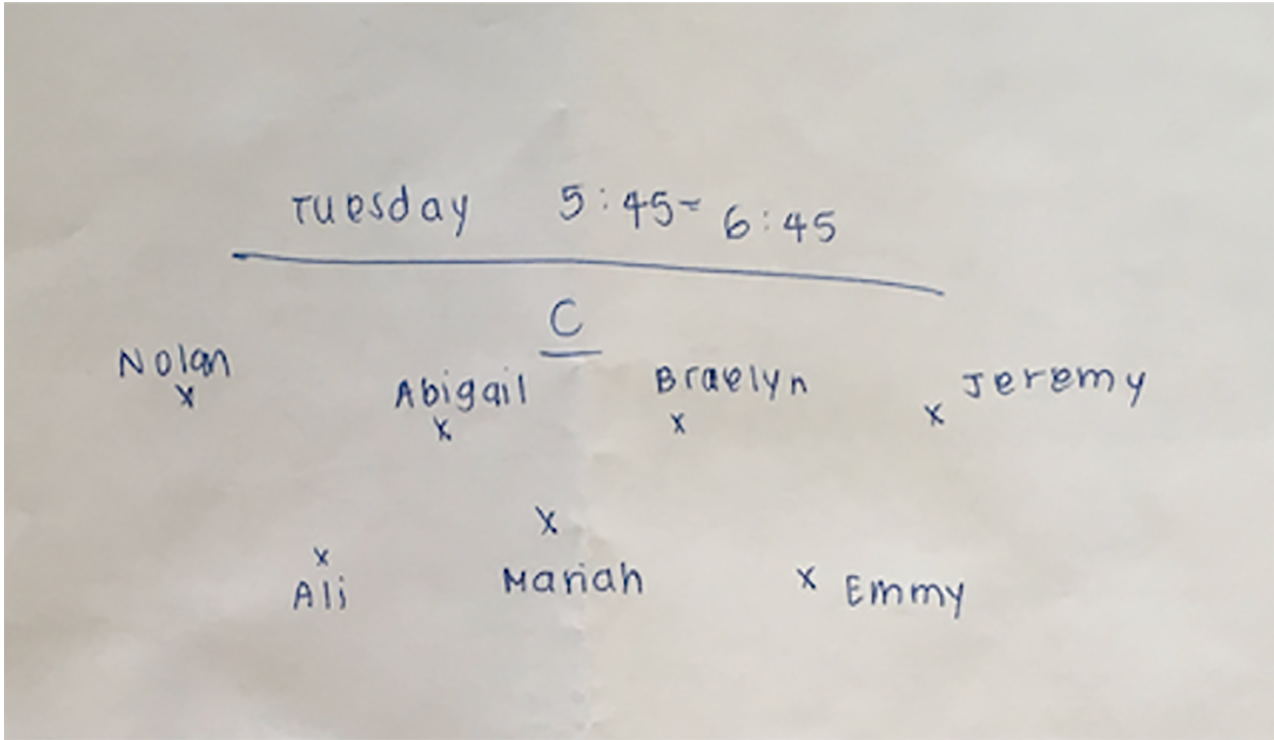

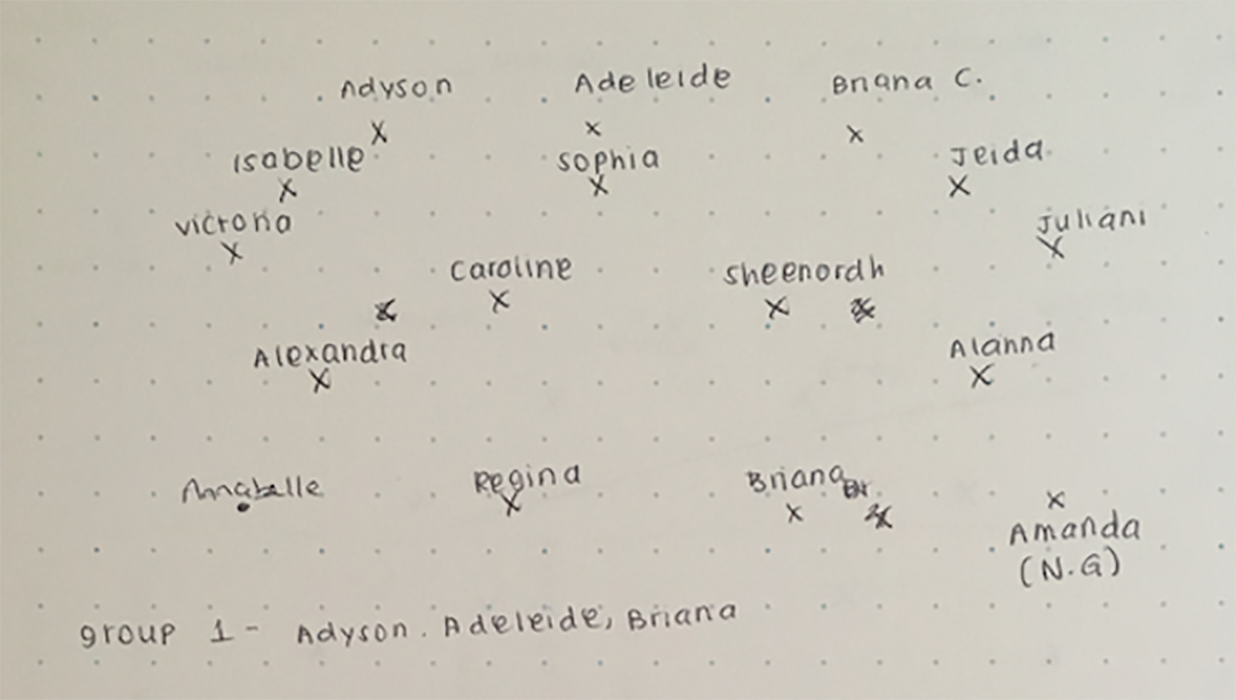

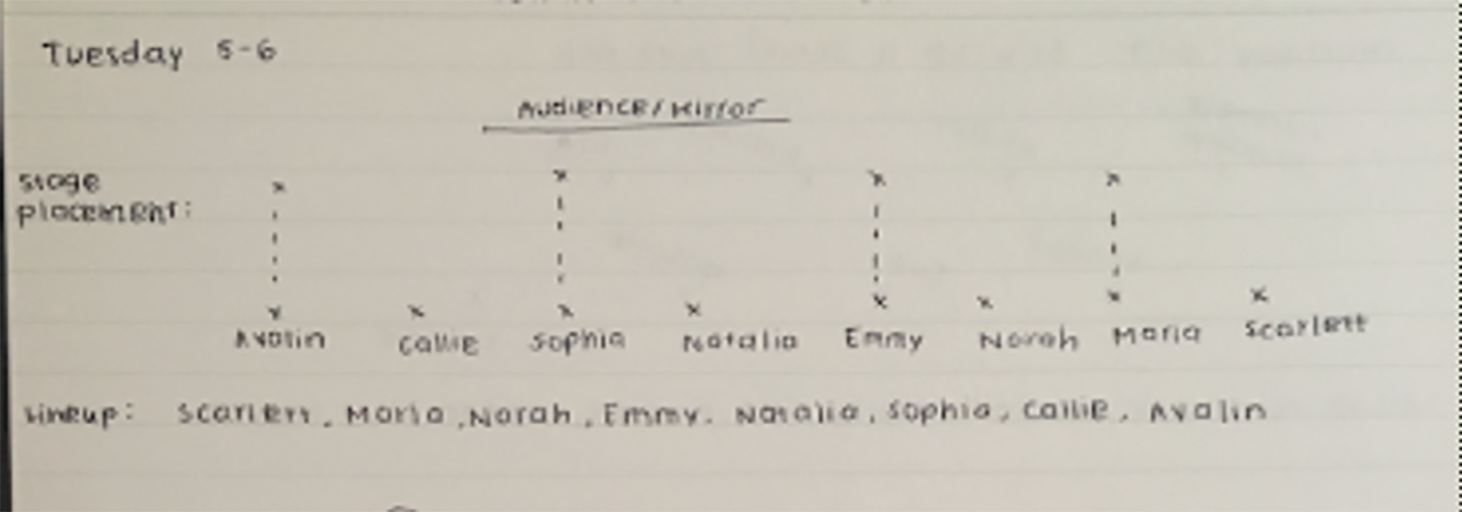

These texts normally begin frantically on the backs of envelopes, coloring sheets, or even the roll sheet for the class. My teacher announces that we will begin the recital or holiday showcase piece, and I scramble to find a piece of paper to write on and a pen from the teacher’s counter. I mark each place where the teacher places the dancer, as well as the mirror and center stage. The example shown in Figure one was made recently when I assisted Erika Galan (a teacher I frequently work with), where I wrote the places for our Tuesday night class on the back of a coloring sheet.

The placement for the dancers is indicated by the “x” and the child belonging to each space is written next to it. The mirror is represented by the line on the top of the coloring sheet, and center is marked with a “c”. Looking at the sheet as a whole, we can see that dancer Mariah is placed center in the back row for the Tuesday 5:45-6:45 class. As I write this paper, these dance notes were created last week, and we have just created the beginning of this particular Jazz dance for the Holiday Showcase in December. It is important to recognize that Erika does not take notes for her formations or choreography, so as I look over these pages I created, they bring a mental image to my brain of what was completed last week. These notes are essential for what I must remind Erika next Tuesday as she teaches the class. As Elizabeth Angeili states when discussing the textual practices of EMTs, “notes then [become an] external representations of individual memory. They decrease cognitive workload… It also helped bridge time” (3).

In the world of a dance instructor, my notes are my way of “bridging time”. I depend on them in my workplace as my inscriptions facilitate my ability to recall dance movements. With these notes, I help Erika continue choreography and plan her classes week by week. In her discussion of dance literacy, writer Ann Dills states, “Both dance and language have, perhaps, developed into symbol systems that allow the reader/watcher to re-visit experience…” (99). Recording dance formations is the first step to creating a dance. Therefore, creating a formation comes prior to choreography. So, formation planning becomes the foundational step in choreographing any dance. Speaking on formation planning as a whole, these texts are functional in that they provide the first initial launching steps for creating a dance; these texts ensure that progress made each week in the classroom will not be forgotten and allow Erika and I to consistently recall the placement and formation of our students.

Taking an even broader scope of “invention” stage of choreography, as seen in Figure 1, these notes reflect the initial draft of any writer’s work. In the chapter “Writing In and About the Performing and Visual Arts through dance”, scholar Molly E. Daniel writes about “… the way the choreographic process engages both the body and mind to create a foundation to expand writing and writing pedagogies” (201). In continuation with the concept of writing and choreography as intermingled processes, it is notable that like both an essay of an academic writer or the choreographic process of creating a dance for the Holiday Showcase, both artists begin with a draft or initial stage that later develop. Where Erika and I began with roughly taken formations recorded on the back of a coloring sheet, author Anson began writing for his son’s football game in a notebook (Anson 525). Scholar Chris M. Anson shows his initial notes of his son’s football game in Figure one of his piece (refer to Figure 1a.), The Pop Warner Chronicles: A Case Study in Contextual Adaptation and the Transfer of Writing Ability. Now, objectively comparing my dance notes to that writing process, it is observable that functionality also lies in facilitating creativity, as the drafting for choreography or even a football article are the first steps to a final piece.

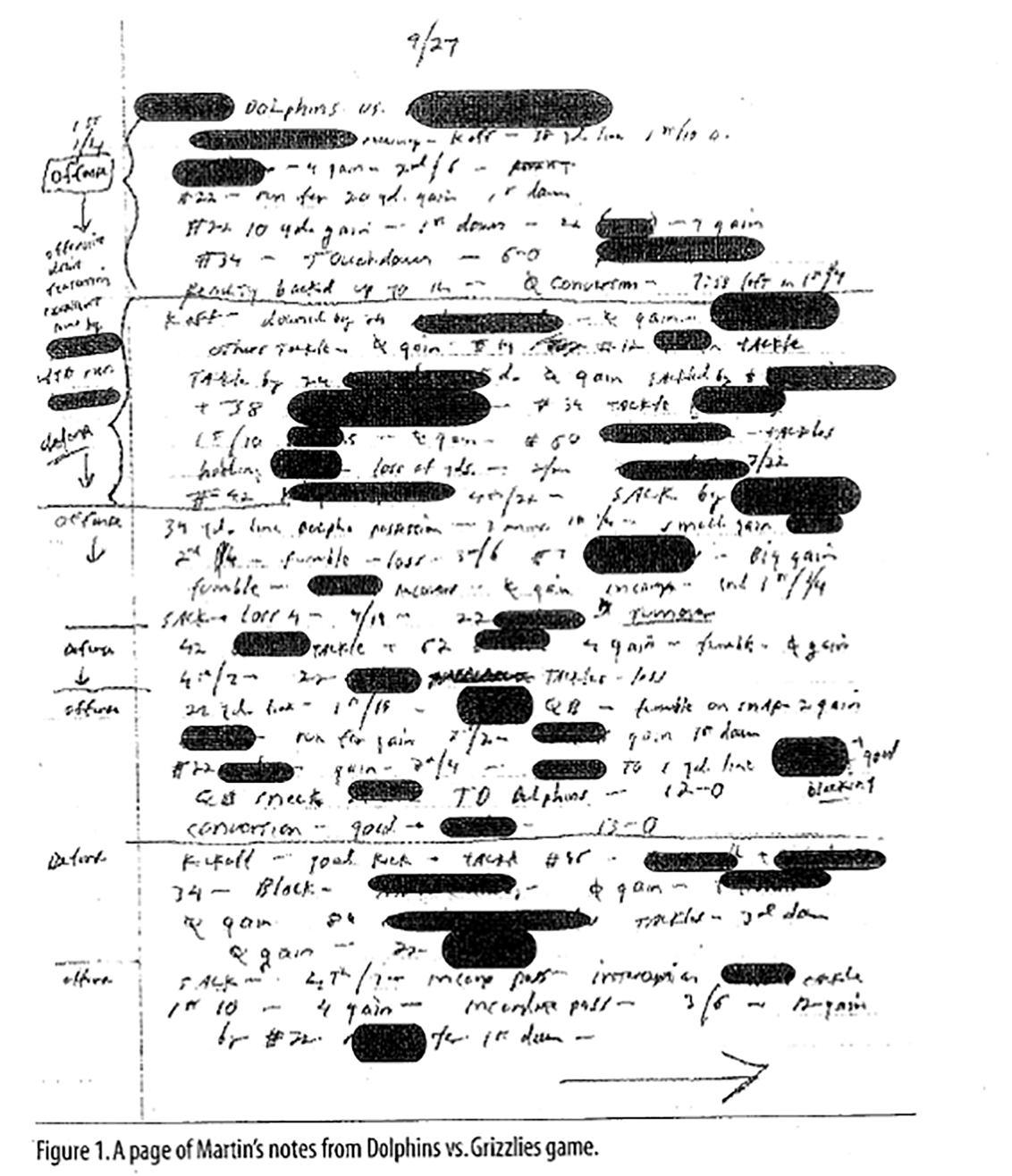

Figure 1a. Anson’s notes from his son’s football game, created prior to writing an article

Revision: The Role of Text in the Choreographic Process

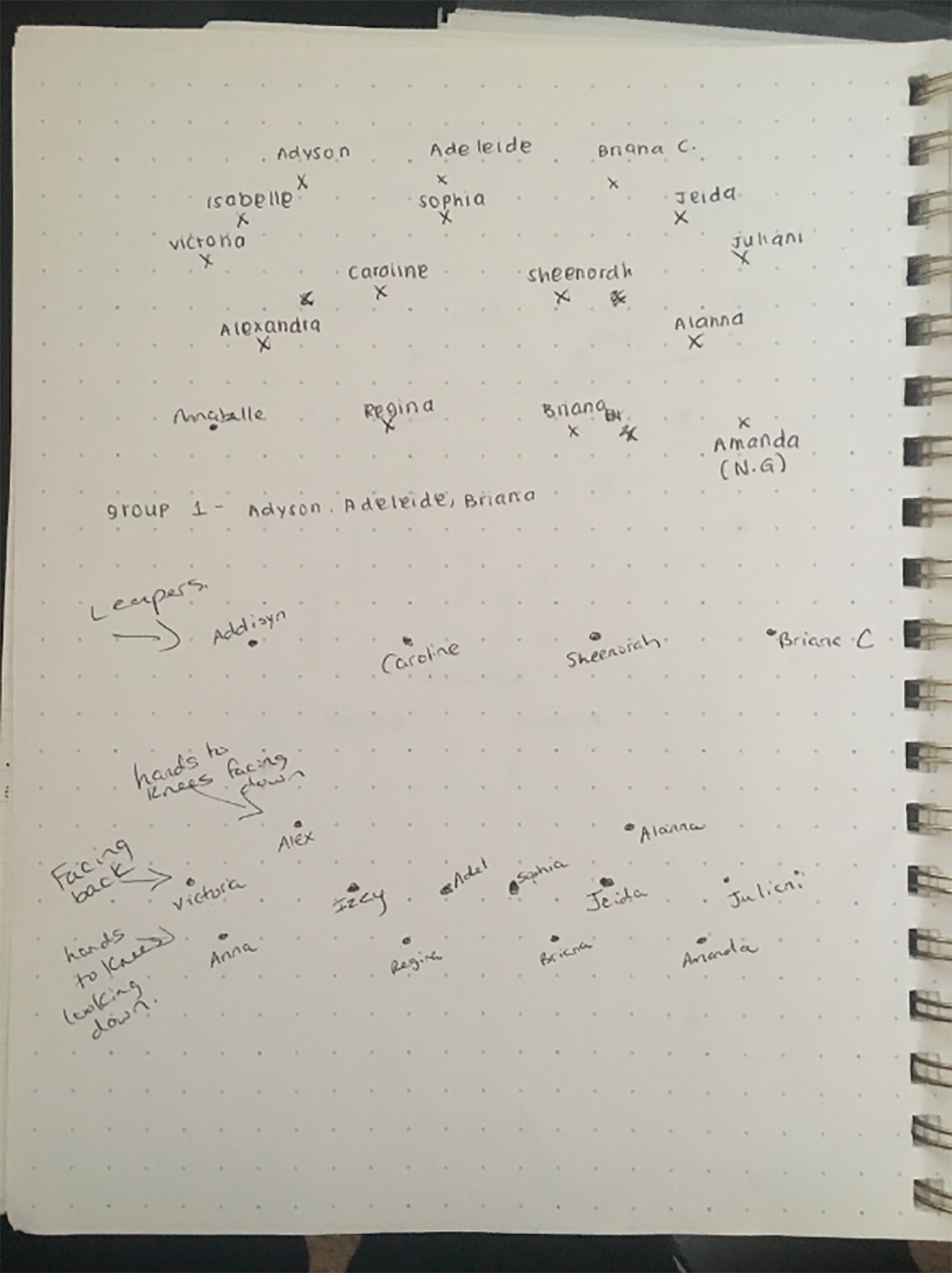

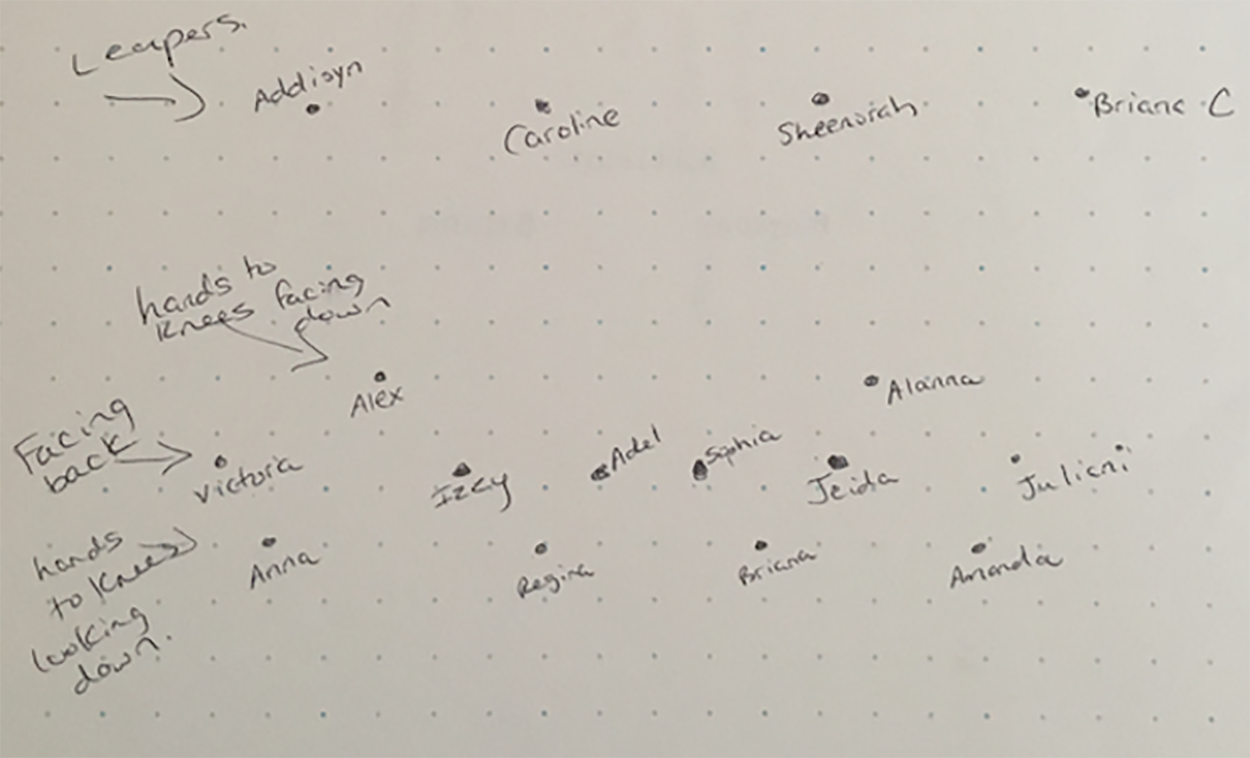

Figure 2. Notes for a dance created with Cara Linguist, in the 2018 school year

After my initial notes, I then transfer them into my planner so that my instructor and I have a stable place to record our dances and mark choreography. In the image above (Figure 2), Cara Linguist (one of my teachers for the 2018 school year) and I transcribed a formation change and choreography that transitioned our dancers from different places on the stage onto a sheet of dotted paper. On the upper half of the page, I recorded the first formation while Cara taught the choreography. On the bottom half, Cara and I met before class to create the second formation as well as the dance steps that will transition the dancers from the first formation to the next. Here, Cara details which dancers will move forward into a straight line to the front of the stage by leaping and the other dancers that will merge into two lines behind them.

With this in mind, these notes were especially helpful as Cara would often leave class early and making me responsible to teach choreography and rehearse the dance. Furthermore, these notes were constantly being added to, and glanced at throughout every class. I would add to this page as Cara taught more choreography, or I would scratch out choreography that was deleted from the piece. Noting how much this page of choreography was reconstructed, these notes were an essential part of the choreographic process of revision. Generally speaking, dance text is functional in that it provides a written form of choreography, allowing the choreographer to experiment and revise their work prior to and while working with dancers.

Additionally, this stage of my notes can be identified as the revision or drafting step of choreography, mirroring the processes writers go through. In the piece, Dancing=Composing=Writing, Molly E. Daniel remarks that “Revision relies upon re-seeing and making changes that arise from a need within the work, which also occurs during the choreographic process. Revision then is enacted by dancers and choreographers reshaping a work before it takes the stage” (205). Overall, choreographing and writing are integrated processes that parallel one another. While, both artforms appear dissimilar, through my notes I observed my dance notes as a sort of essay for a choreography. I write my initial draft of a dance and then this draft is then worked on by my coworkers in a way a teacher corrects an essay. Cara and I reconstructed and edited our dance, physically as well as textually. I created the draft (refer to Figure 2a), then my coworker continued and corrected my work (refer to Figure 2b). Placing dancers, recording choreography, and noting dance movements through text highlights how the textual processes of writing are transferable into the discipline of dance.

Figure 2a. The portion of the Jazz dance I recorded during class time. An enlarged image of the upper half Figure 2.

Figure 2b. The Portion of the Jazz dance, my coworker, Cara Linguist created and noted prior to class. An Enlarged image of the lower half of Figure 2.

Performing: Finalizing Text to be Read in the Wings

“Text for The Dance Dads”

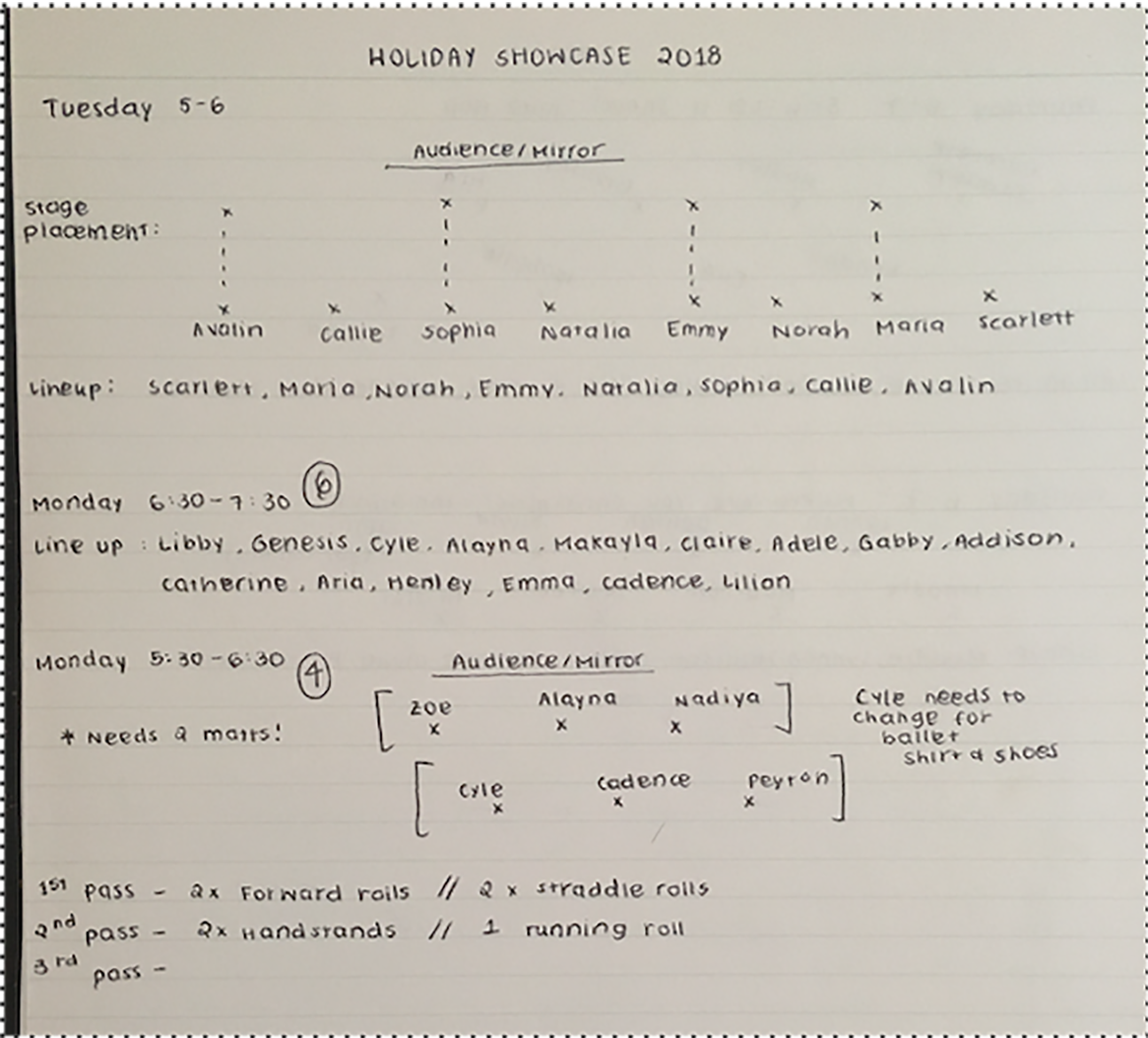

Figure 3. Holiday Showcase 2018 Notes created while assisting Erika Galan in several dances. This is the overall page of notes shared amongst the “dance dads” behind the stage

The chaos of showtime, at a recreational studio is absolute mayhem. My dance studio rents out University High School’s auditorium every year for the Holiday Showcase. Each year parents are wildly running up and down the hallways as they nervously send their frightened three-year old children to be launched on stage for the first time. Noise echoes in the dressing rooms as older company dancers fling their legs around rehearsing minutes before performing. In the midst of the craziness, “Dance Dads” are hauling tumbling matts on and off the dark stage to keep the show running.

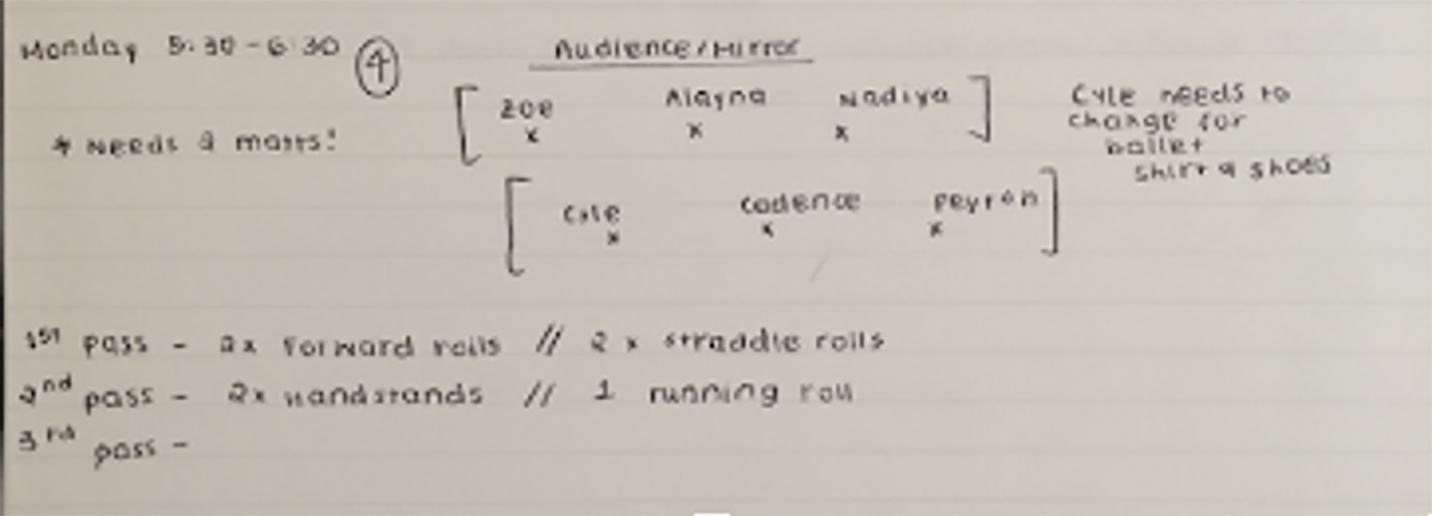

Figure 3a. Monday 5:30-6:30 class notes. This dance was created in collaboration with Erika Galan. This is an enlarged image from Figure 3.

Figure 3a is an example derived from another dance created with my coworker, Erika Galan. However, these notes were not created for me, but rather to demonstrate how the “Dance Dads” should prepare the stage for this tumbling performance. On the left-hand side, I write with an asterisk “needs 2 matts!” and accompanying this are two brackets with the names of children. These brackets represent the way the matts should be set up on stage prior to the performance. Looking closer at my notes, you can see the number four written next to “Monday 5:30-6:30”. This number symbolized this dance’s place in the number of performances for the evening. This dance would go on stage fourth, and so in an attempt to give the people behind the stage an organized layout for this class’s performance, I made it clear when these notes should be used on the performance day.

Acknowledging that my notes surround choreography, they also serve as a functional tool for a guideline in the setup of the stage. As quoted by Daniel in her piece, Dancing=Composing=Writing, “...performance functions as two differing concepts, ‘one involving the display of skills, the other also involving display…” (207). While Daniel may have used this excerpt to demonstrate the body as a conduit for delivering a final performance, this quote is valuable in the context of stage production. It is important to recognize that the matts placed correctly on stage directly contributes to the success of our dancers’ performances. Therefore, my notes are highly valued from the moment they were invented to the moments before our dancers walk on stage. Figure 3a showcases the functionality of dance text not only for my choreographic purposes but also for the ultimate goal of translating our dance from the studio to the stage.

“Text for Teachers and Assistants”

Figure 3b: Notes created for a tap class, to be performed at the Holiday Showcase 2018. This dance was created in collaboration with the studio director, Cara Linguist.

In addition to the “Dance Dads” loading matts on and off of the stage, teachers and other assistants scurry in the blackness of the wings to put their dancers in line order so they could all link hands and walk quietly to their assigned spots. In the craziness of show day my thoughts and adrenaline are sporadic. During the 2018 Holiday Showcase, I jumped on and off stage without a break. I can recall having more than nine dances back to back where I would line up my dancers, dance on stage with them, then walk them back into the wings just to repeat the process all in the seconds break between numbers. So, I often clung to my notes for safety and reassurance that I did not place a child in the wrong spot, or nervously passed my notes to another assistant so they can help me line up my dancers.

In sum, I utilized my dance notes even during the most crucial part of choreography—performance. Writer Ann Dills states in her article, Why Dance Literacy? “Performance simultaneously confirms and undermines the text. The body of the actor, like the body of the text, stumble into ambiguity, insinuating more than words say with gesture, movement, intonation” (99). As a writer goes through their processes of invention, and revision, a final draft is created. In the case of a dancer, all rehearsals culminate into a final performance. Above all, dance and the writing processes are mirrored through each step of creation. Moreover, speaking on the functionality of my dance text in this final stage, my notes were heavily relied on as a means to recall all the work created in the studio. They allowed me to move smoothly and quickly between numbers, and also allowed me to communicate with other assistants and teachers behind the stage to help create a sense of organization amongst all the chaos behind the stage.

Conclusions and Implications: Text in the Dance World

As a dance transforms from studio to stage, so does the text that accompanies it. At a glance, most people would not assume that text plays such a vital role in the creation of choreography. Furthermore, the similarities between the processes of drafting a dance and drafting an article of text became abundantly clear through each step of creation. Dance and writing are artforms that parallel one another in a multitude of unrecognized ways. More than this, each art form gives way to one another, as stated by Corbrett in his article, Writing In and About the Performing and Visual Arts Creating, Performing, and Teaching, “...motion gave way to emotion, which in turn gave birth to mutual understanding … of writing” (220). Writing and dance are coupled artforms that are rarely recognized as one in the same. While dance is a very physical artform, the role of text is a vital tool for the creative processes of choreography. As observable throughout this paper, my personal study reveals that dance inscription is a functional practice in my role as a dance teacher as it serves as a memory, collaborative, and performance aid, which ultimately increases the confidence I present myself at work.

While my account covers the many stages of dance inscription throughout choreography, future analysis can be broadened by altering the amount of time and studying professional notation for further understanding of the functionality of dance text. For instance, professional dancers have designated notebooks to help remember an abundant amount of choreography as well. A former soloist with the Royal Ballet in London stated in her video How to REMEMBER CHOREOGRAPHY, “I used to have a book where I wrote down all the ballets… I used to word it step by step… and I would make sure I would have it at the studio with me, so I could look back at it” (3:44). Professional ballet dancers often learn multiple ballets in a short period of time as company dancers work seasonally and must note take for a different purpose than my own. Where I studied my notes of a dance for choreographic purposes, professional dancers create notes for the singular purpose of performance. Furthermore, altering the time that these notes take place can also offer an alternative perspective of the functionality of dance inscription. My study followed notes created within a two-year time span. As stated previously, professional dancers work within a season, and so studying their notes within a single year time period can offer insight into their intensive memory processes and the diagrams that capture their place amongst dozens of dancers as opposed to single class, as seen in my personal research. Speaking broadly, expanding the scope of the study so that professionals with a longer time period of research could enhance the observation of dance text even further.

On the whole, it is important to recognize the intent of my notes to help my recreational students perform an entertaining piece for the parents as well as provide cognitive support for myself and my coworkers during class time. When I started my job as a teacher at my childhood dance studio, I did not expect text to play an integral role in my daily activities. By analyzing the work I created in the past couple of years, I found that my growth as a teacher is captured in my ability to take notes. These notes contributed to how I taught choreography, reconstructed dance movements and formations, and even changed the final seconds before stepping on stage. Text in the world of dance, is largely unrecognized as a choreographer’s text, is like the drafts of a publication for a writer. Therefore, my research fills the need to understand the role of physical dance inscriptions in the realm of dance. By collaborating with others and consistently editing the rhetoric of a dance, I found that the textual processes