“Ok good, have a seat choir.” I take a seat and grab my pencil, preparing to mark the notes I know my choir teacher is about to give. She asks us to sing again, telling us to crescendo and sing with more space. I draw a less than symbol, indicating where she wants us to crescendo. I look at my music while she asks only the sopranos to sing, isolating their part on the piano. I’m ready when she asks us altos to join them. The pianist plays our part, and my teacher sings the soprano part so that everyone has someone to listen to if they need help finding the correct note. “Great job! Let’s stand and start from the beginning.” I stand, holding my pencil, and take a deep breath, ready to sing.

Any typical choir practice involves more talking about the music than actually singing. We rarely sing the piece for its full duration because my director is constantly stopping us to give notes. Singing in a choir is a deeply literate activity. There is much more involved than singing notes on a page. I use several inscriptions to help myself sing the correct notes. I make notations throughout my music to help me remember diction and how to make phrases more impactful. While technicality is important, evoking emotion from an audience is more important. My graphics and writing in sheet music are essential because they help me sing accurately and emotionally, allowing me to connect with the audience.

For this analysis, all of my inscriptions are on a major work by Andrea Ramsey entitled Suffrage Cantata. The UCF Soprano Alto Choir was invited to join a mass choir to perform this song in Carnegie Hall in April of 2022. Ten of us sang with sopranos and altos from across the country in a choir that was about a hundred singers total. I spent most of the Spring 2022 semester learning the piece. It tells the entire story of the woman’s suffrage era across five movements and includes real texts from suffragettes like Susan B. Anthony and Ida B. Wells Barnett. It features narration as well as singing. In addition, the narrator has solos throughout the work, taking on the role of suffragettes like Sojourner Truth. This intertextuality helps to give century old quotes a new life and educate audiences through beautiful music. We were all inspired by the subject matter and wanted to share the untold history of the women’s suffrage movement.

Often, chords and harmonies create sound, meaning, and feeling that go “beyond words,” as Komysha Hassan discusses in “More Than a Marker for the Passage of Time.” Suffrage Cantata is a deeply emotional piece. Many harmonies and chords “go beyond words to communicate and express” (Hassan 1) the grim reality it describes at times. The very end of the piece is a wonderful example of how even a single chord can say so much. The last measure is piano only, after the choir has finished singing their final note, and the ending chord has an eerie sound. When we got to talk with Dr. Andrea Ramsey, the composer, and ask her questions about her work, she said that the eerie sound of the final chord is intentional. It communicates that the movement Suffrage Cantata describes is not over yet. The piece doesn’t have a satisfying end for this reason.

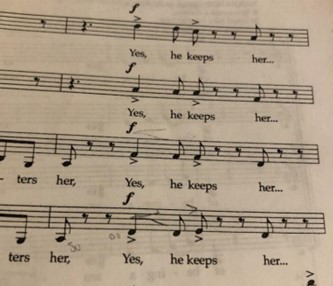

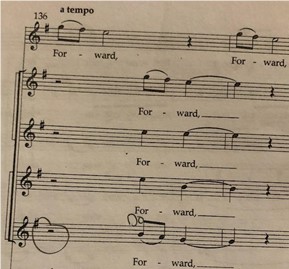

Ex. 1. Andrea Ramsey, Suffrage Cantata

Frequently, I write or make graphics to remember and sing accurate pitches. Mike Rose defines “graphics” in “At Last: Words in Action” as “a whole array of esoteric symbols… workers often generate [graphical] illustrations themselves” (126). I tend to write in solfège for skips. Do, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, Ti, and Do are the solfège counterparts for pitches of a scale. A skip involves two notes that are more than a whole step apart. Singing Do then Mi is an example of a skip. Usually when I write in solfège it is for a So to Do skip, as shown in example 1. I often sang this skip in warmups for choir in high school, so it is the easiest for me to hear internally. If I don’t write these notations, I will most likely end up forgetting the distance between the notes and singing incorrect pitches. Doing the corresponding hand signs helps me sing the pitches correctly, too; Do is a closed fist and So is an open palm, with your palm facing inwards.

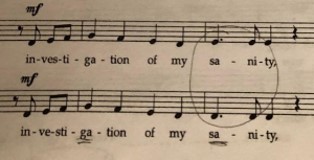

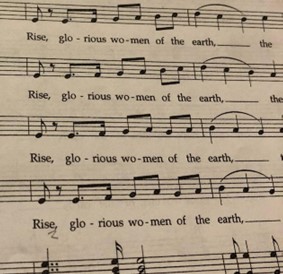

Ex. 2. Andrea Ramsey, Suffrage Cantata

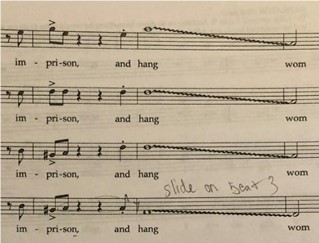

A graphic I often use when I need to pay attention to something is a simple circle. I tend to circle particularly difficult skips, for example, and for this piece I often circled notes when my part creates a dissonant chord with another part. Suffrage is an SSAA piece, which means it has four parts: soprano one, soprano two, alto one, and alto two. Sopranos sing higher notes and altos sing lower notes. I sing alto two. In example 2, my pitch is a D and the alto ones sing an E, which is only a whole step above, so when we sing together it creates an eerie sounding chord. I circled this to remind myself that this crunchy sound is actually the correct pitch. I also underlined “ga” and “sa,” shown in example 2, to remind myself that those are the syllables I should place emphasis on when I sing. For complex parts such as sliding in harmony, I write in short reminders for myself (see example 3). A slide is when, instead of skipping from one note to the next, a singer sings all of the notes in between. A slide in harmonies can easily sound chaotic and incorrect, but everyone sliding on the same beat creates the right effect and sound. It would be very noticeable if even one singer slid on the wrong beat, so this inscription is essential.

Ex. 3. Andrea Ramsey, Suffrage Cantata

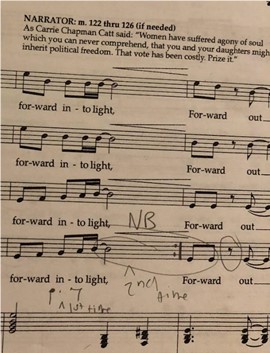

Sometimes conductors make slight rhythmic modifications to a piece, such as shortening the value of a note and adding a rest. I draw these in my music so I remember the change. In example 4, a repeat was added so that the soloist would have enough time to read her narration before needing to sing. We changed the rhythm for the first repeat and added a no breath line, indicated by the common choir inscription “NB,” for the second. Instead of singing a half note the first time, I sing a dotted quarter note followed by an eighth note rest, as shown by my graphic in the same example. In “At Last: Words in Action,” Mike Rose discusses functions of writing of a limited sort, saying that “Writing of a limited sort… [can be] written as a memory aid” (127). This writing of a limited sort is shown in example 4, and it helps me to remember the repeat, not to breathe between those notes, and the changed rhythms. Graphical inscriptions such as these are essential to make sure every choir member is aware of changes, and no one sings the wrong note.

Ex. 4. Andrea Ramsey, Suffrage Cantata

Silence can be just as important to music as singing, so I also tend to circle rests. If I were to mistakenly sing in a rest when no one else was singing, I would disrupt the unity of the choir. Rests are also important for emphasis. For example, the eighth note rests I noted in example 4 help to emphasize the words and the diction of the syllables. It is also important to rest if a soloist is singing, like in example 5, where I circled the rest so as not to interrupt simply because I was not paying attention.

Ex. 5. Andrea Ramsey, Suffrage Cantata

Popular singers like Ariana Grande have been criticized for being difficult to understand, which is why correct diction is so important. Many of my inscriptions are related to it. Some remind me to make sure the correct consonants come out for the audience so that they can understand the lyrics. As shown in example 6, I wrote a Z under the word “rise.” This may not seem significant, but remembering a Z sound instead of an S sound ensures that “rise” is said correctly. I do not want the audience to hear “rice” instead. That brings me to another reason proper diction is so important, which is so the impact of a phrase reaches the audience. At this moment in the piece, the suffragettes celebrate victory. The Z sound, by ensuring the word “rise” is heard, emotes this victory for the audience.

Ex. 6. Andrea Ramsey, Suffrage Cantata

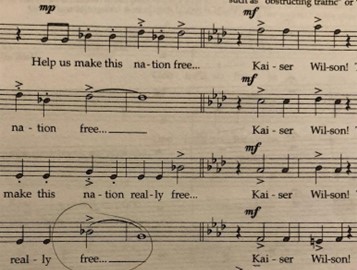

In example 7, the dynamic marking changes from “mp” to “mf,” which means to sing louder. This indicates that the upcoming phrase is important and should be sung as such. “Kaiser Wilson” is a significant name to call the president of the United States, so the K needs to be emphasized, which is why it is underlined. This simple marking reminds me to emphasize the syllable to convey the strong intention behind the suffragettes who first said this to the president.

Ex. 7. Andrea Ramsey, Suffrage Cantata

The markings I make in my sheet music serve as my reminders to sing the correct pitches and rhythms. They help me with diction and with making phrases more impactful for audiences. Using them, I can evoke emotions from audience members with my musicality. I can take them through the women’s suffrage movement with diction and the way I sing certain phrases. A quote from Hassan captures this idea perfectly: “There was so much to say… but with very little words that could express [it]” (2). This is where music comes in. Combining text with rhythms and chords creates a meaning that goes beyond words. The final chord of Suffrage Cantata says so much in just 4 beats, leaving the audience with a deeply emotional message. Listen to the clip of the ending and the piano chord, below, so you can experience the same feelings yourself.