Tarot cards are decks of playing cards used for divination and cartomancy, practices to see into the future, and gain insight on a situation. These cards are typically used in tarot reading, which is defined as “the practice of divining wisdom and guidance through a specific spread (or layout) of Tarot cards” (“What is Tarot?”). Although they have been around for hundreds of years, public interest in tarot cards’ has increased in recent years. With the uncertainty and fear incited by the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, people sought out the counseling capabilities and foresight into the future that the cards provided. In the following essay, I will investigate the mechanics that shape the genre of tarot cards–and by extension tarot readings–to discover how they are useful not only in times of distress, but in everyday life.

Features of Tarot Decks

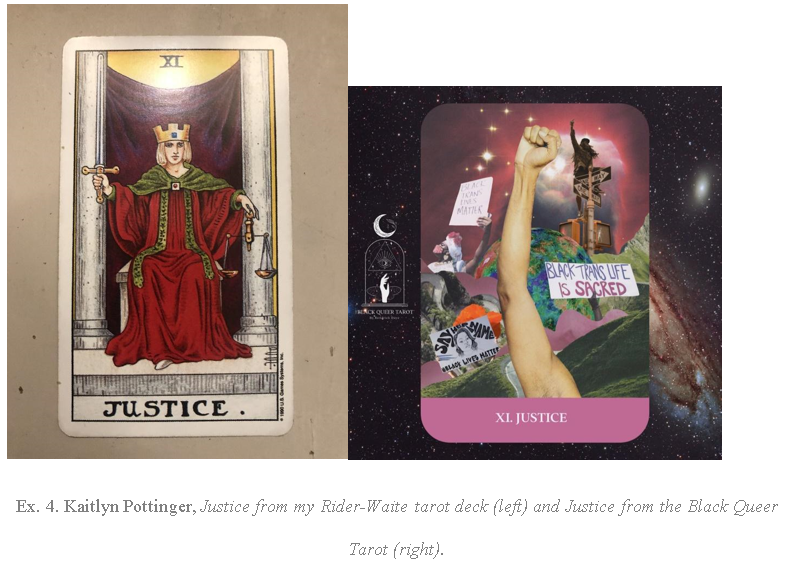

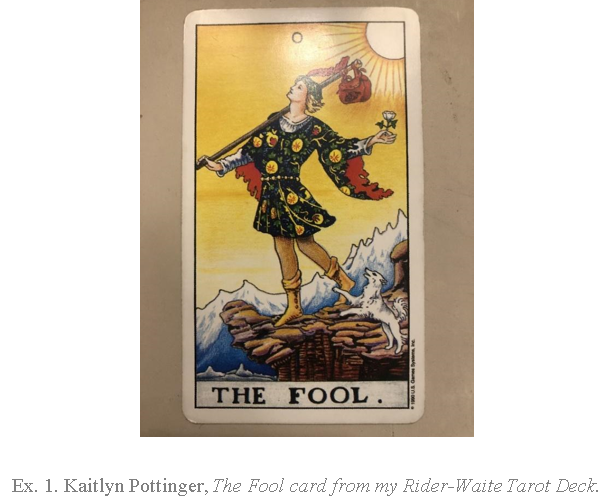

In the article “Navigating Genres”, author Kerry Dirk explains that genres contain attributes that construct the genre itself, establish expectations, and differentiate it from similar genres (249-251). For instance, tarot cards are often compared to oracle cards and standard playing cards. Although tarot decks share similarities with the two, there are characteristics that establish a clear distinction. This includes the Major Arcana and Minor Arcana. The Major Arcana cards are often recognized even by those who are not familiar with tarot cards; The Devil and The Lovers cards are a few of the well-known ones. Individually, these cards represent universal human experiences, life lessons, and karmic influences that provide insight in times of need. When united, the 22 cards tell the story of The Fool–the first card in the Major Arcana lineup–and triumphs, trials, and tribulations he faces throughout his lifetime. The tale is meant to reflect the human condition and the encounters that shape our life journey. When a Major Arcana card appears in a tarot reading, it typically establishes the context and overarching themes the other cards will relate back to.

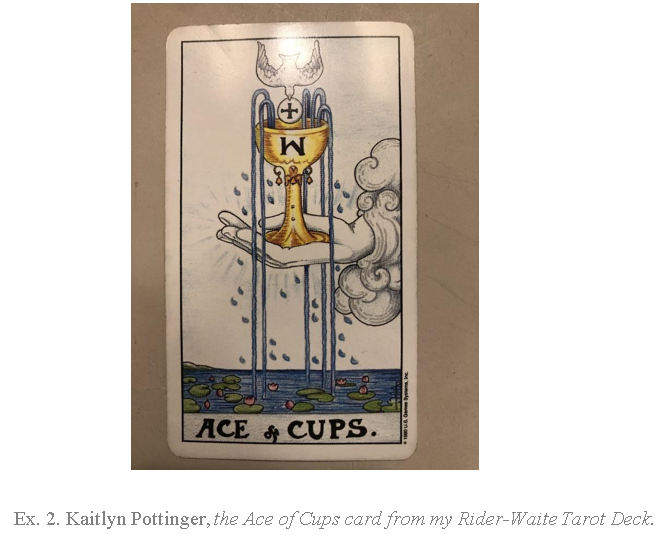

The remaining 56 cards in a standard tarot deck are comprised of the Minor Arcana, which, as opposed to the bigger picture painted by the Major Arcana, “relate to what's happening in your daily life, and can offer insight into how your present situation is affecting you and what steps you need to take to manifest your goals” (“Minor Arcana”). There are four suits in the Minor Arcana: cups (representing emotions and creativity), wands (representing motivation and passion), pentacles (representing finances and material possessions), and swords (representing thoughts and actions). Each suit has ten numbered cards and four court cards (knight, king, queen, and page). The Minor Arcana cards describe short-term influences—situations that can easily be changed depending upon one’s course of action.

The History of Tarot Cards

It is important to discuss how tarot cards came to be in order to understand their contemporary uses, especially in tarot readings. Tarot’s humble beginnings were quite secular when compared to its modern spiritual ties. Its ancestry can be traced back to 15th century Italy and France where artists were commissioned by wealthy patrons to create heavily illustrated playing cards for parlor games like tarocchi (L; Wigington). Initially, these decks only contained 56 cards with four suits–wands, cups, swords, and coins–which would later become the Minor Arcana. The earliest versions of Major Arcana developed when rich families recognized the prestige of owning triumph cards, or customized cards with illustrations of family and friends, which were added alongside the original suits.

Tarot became a divinatory tool when in 1781, French Freemason, Antoine Court de Gebelin, “published a complex analysis of the Tarot, in which he revealed that the symbolism in the Tarot was in fact derived from the esoteric secrets of Egyptian priests” (Wigington). His claims were further solidified by “Eliphas Lévi, author and former Catholic priest, [who] popularized the notion that tarot symbols were somehow connected with the Hebrew alphabet, and thus to the Jewish mystical tradition of kabbalah” (Wigington). Although these statements had little to no historical basis, many Europeans believed them to be true, and by the nineteenth century, it was normalized for playing card decks to be manufactured with artwork based on the writings of de Gebelin.

Just as Dirk pioneered a new method of teaching genre to students in her article, “Navigating Genres,” in 1791, French occultist, Jean-Baptiste Alliette, made the first divinatory tarot deck–the ancestor to the many decks used in the present-day. “Someone must create [the] first response” to a new rhetorical situation (Dirk 252), and Alliette established a precedent that catalyzed a recurring response. Now, there are various types of tarot decks whose designs are deeply intertwined with the spiritual and intellectual climate at the time of their initial creation.

Tarot Reading in Action

To demonstrate the practice and further explore ideas expressed in my genre study readings, I performed a personal single-card tarot reading. The prompt I chose is “What is today’s challenge?” Before delving into the reading, I deciphered the rhetorical situation to understand what this spread is trying to accomplish. The reading’s exigence, or “the circumstance or condition that invites a response,” is to address my concern about obstacles that could arise during my day (Bollin Carroll, 48). The one-card pull structure asks me to trust the deck’s response as a credible source despite being constrained to the influence of a single card. My responsibility as the rhetor and audience is to translate the spread’s response, decide whether the answer resonates with me, and, if it does, figure out how it can help me prepare for a potential conflict.

Holding my cards in my hands, I set the intention for my reading by thinking about my question and allowing for any thoughts answering my inquiry to arise. Tarot reading relies on intuition, so it is not uncommon to have a “gut feeling” about the deck’s response. Speaking aloud, I posed the question to my deck then overhand shuffle my cards. The first card to fall out of formation was The High Priestess, a Major Arcana card. Once I started to interpret this card, the tarot deck transitioned from being an impartial object to a site of what author Anis Bawarshi calls a genre performance, where the material contexts contriving a particular genre are subjected to “temporal, interdiscursive, interpersonal, and ideological relations” (Beyond the Genre Fixation: A Translingual Perspective on Genre 244).

Tarot cards are a form of visual rhetoric, which “refers to any communicative moment where visuals (photographs, illustrations, cartoons, maps, diagrams, etc.) contribute to making meaning and displaying information” (Cohn, 21). Like many other cards, The High Priestess contains few words; therefore, meaning is generated predominantly through images, which allows for interpretation and makes the cards applicable to various situations. Visual rhetorical analysis encourages tarot readers to exercise their intuitive abilities and deductive reasoning to draw conclusions in concert with the reading’s purpose.

The card’s distinction as The High Priestess is supported by various symbols. The crown, cross, and throne reflect her divine authority as ruler of the conscious and subconscious mind; these two realms are signified by the pillars’ contrasting colors. Her jurisdiction is further reinforced by the crescent moon, a figure of intuition, laying at her feet, and the partially veiled scroll in her hand labeled TORA, meaning instruction or law. The structures “B” and “J” which the Priestess is situated between mimic the pillars Boaz and Jakin at the entrance of The First Temple of Jerusalem, indicating that this is a sacred space. Pulling The High Priestess alerts the recipient that they have been chosen to enter this space and receive the Priestess’ counsel. This makes the reader feel special, like the universe sent this message specifically for them. Constructing the Priestess as an honorable religious figure whose wisdom is derived from divine powers, garners respect from the audience, compelling them to trust what she has to say.

Receiving the High Priestess means that listening to my inner wisdom is today’s challenge. Tough decisions may arise, but the Priestess implores me to trust my intuition to find solutions. I personally resonated with this advice as I am a person who frequently makes decisions against my gut and later regret doing so. Although only one card was pulled, this shed light on an overarching issue permeating my everyday functions. With this knowledge in mind, I can make strides to remedy this matter or bring these concerns to a mental health provider.

Beyond Advisory: Tarot as Site for Social Reform

Tarot cards are not always warmly welcomed. Many people are intimidated by or even shun the use of tarot cards due to the misconception that they are reserved for those with magical affiliations. However, tarot “is not a closed practice and should remain accessible to all—especially [after its] gain in popularity in isolating times” (Douze). Through genre analysis, this essay encourages those curious about taromancy to partake in it by displaying the merits of tarot as a form of self-care. Increased involvement bolsters the unifying and transformative properties these cards hold. Tarot culture is historically situated in Eurocentric and Western ideals, but having a diverse population of tarot-wielding individuals allows for more inclusive representation and interpretation. For example, The Black Queer Tarot combats the Western heteronormative conventions of the Justice card by integrating elements from a Black Trans Lives Matter protest to give the Justice card new meaning (Douze). Since taromancy is a malleable and subjective form, tarot readers can inject their own interpretations into their cards’ introspection to better suit their reality or situation. By expanding the tarot community, tarot cards’ capabilities include not only predicting the future but building it.